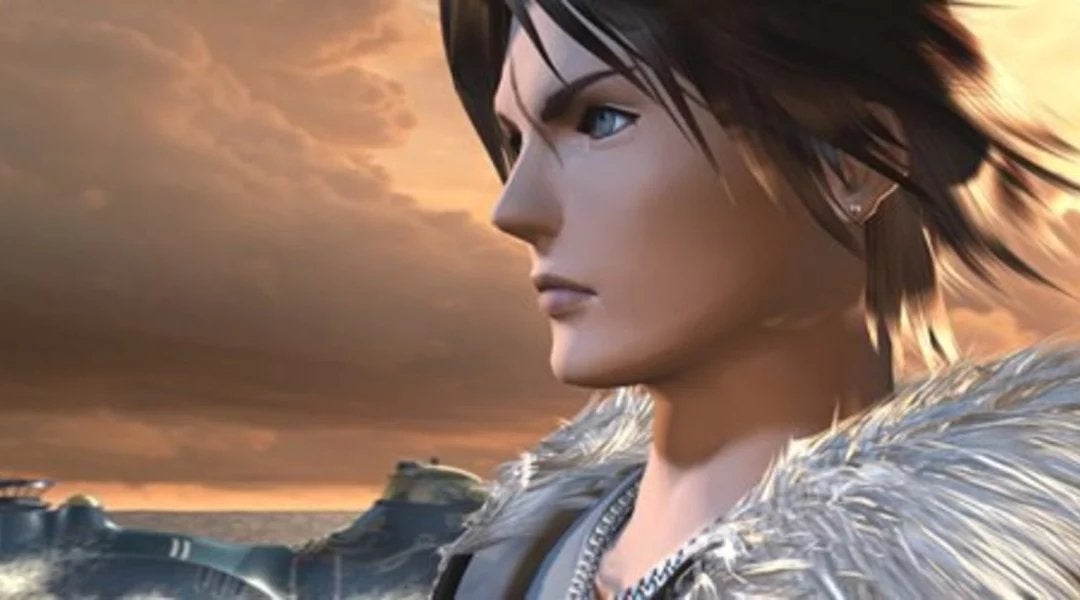

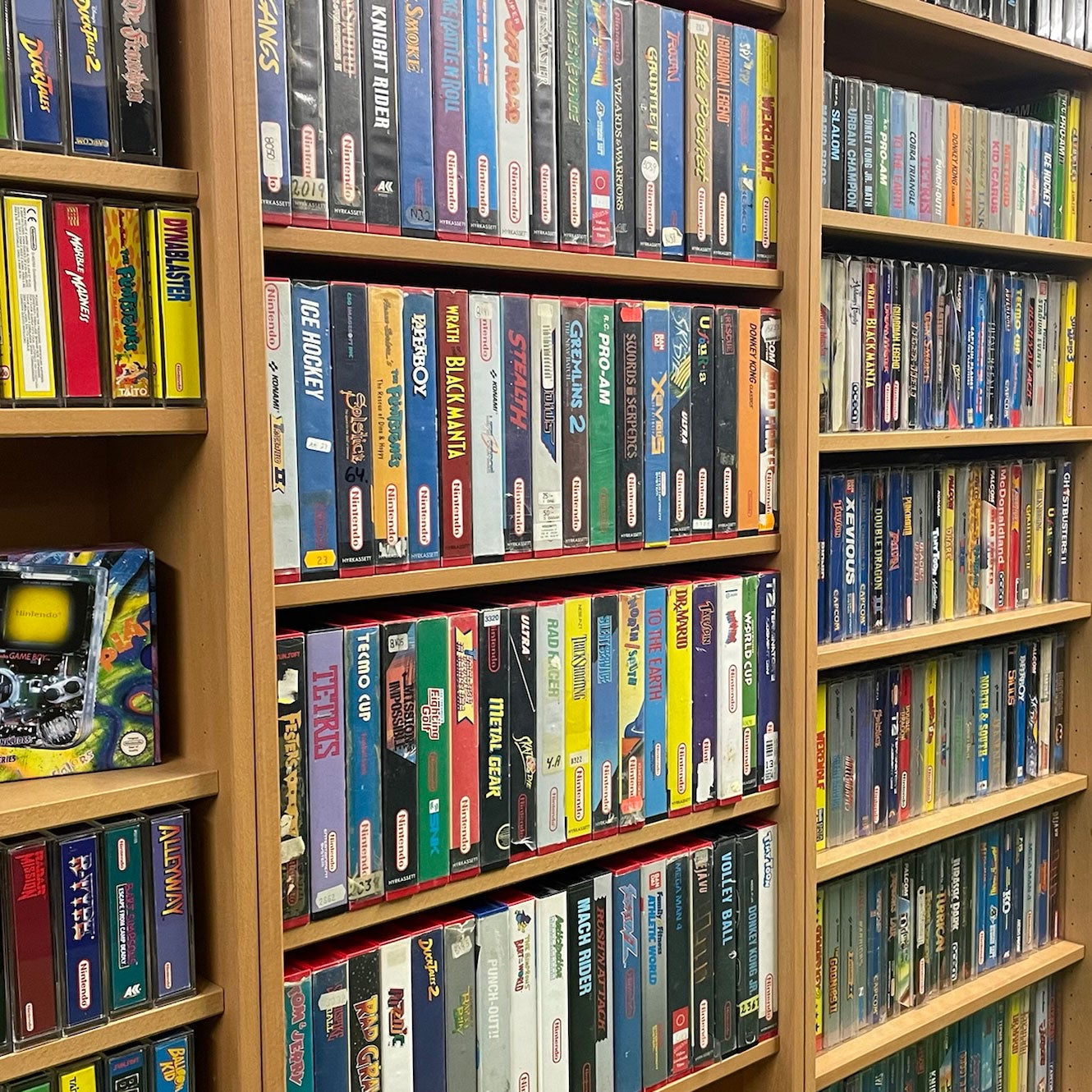

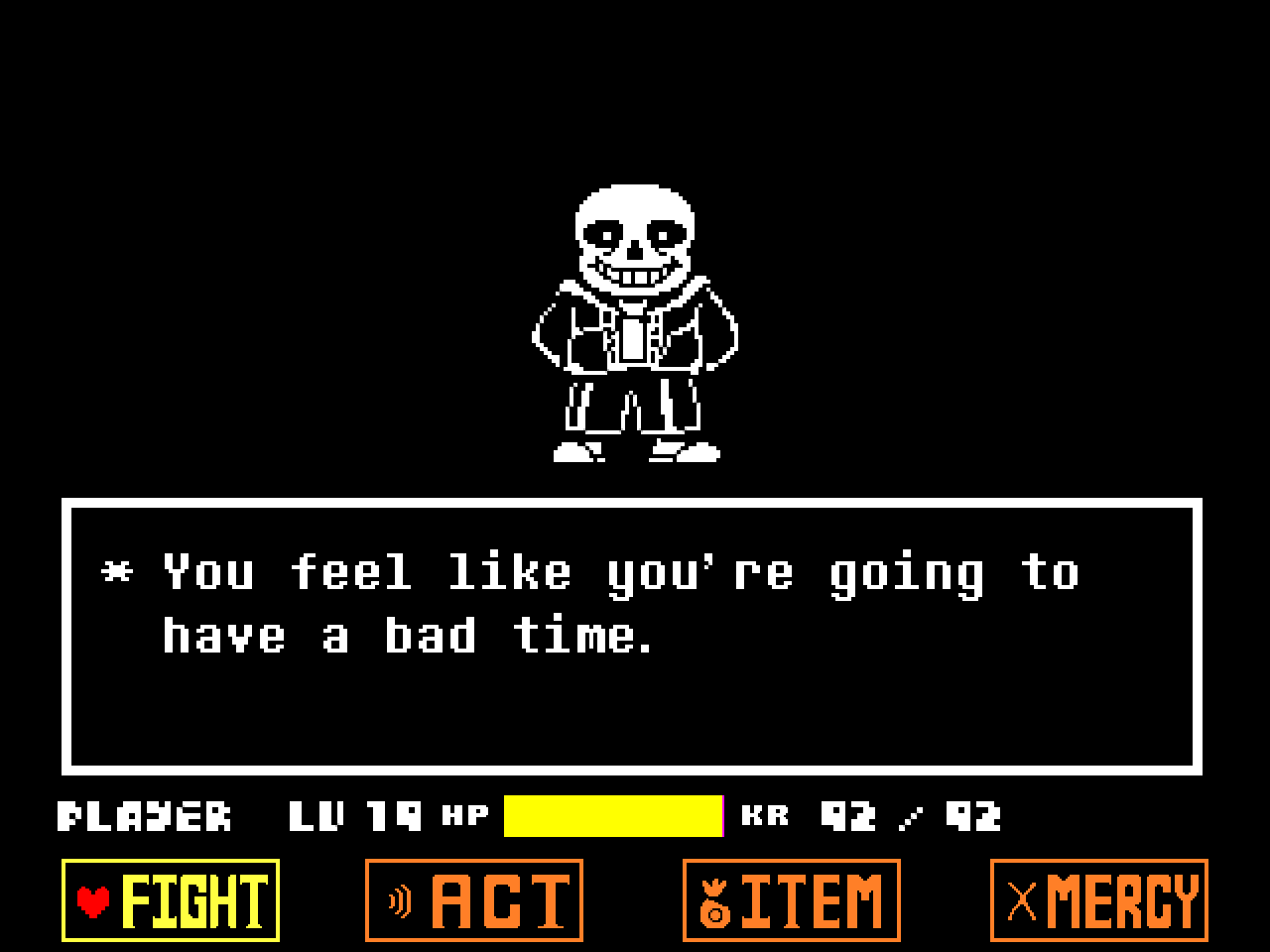

Toys For Bob developed a tool called “The Spyro Scope,” which allowed the team to pull data on each game from the original trilogy as it was running – giving them every variable they would need to stitch each title back together and tap into the authentic Spyro experience. After release, Activision noted that the trilogy had a “successful launch,” and that it highlighted “the enduring nature of Activision’s classic franchises”. The everlasting economic power of nostalgia had been proven once again. Whilst the Spyro Reignited Trilogy was a standout success, its story of lost source code and development materials is a common one in the games industry. Game assets end up lost, destroyed, or unretrievable – forcing remasters, remakes and reboots to find their own ways of recreating a game, or preventing these projects from even getting off the ground in the first place. This is why preservation is so important, as whilst you can’t know for certain that you’ll need source code and assets decades later, you’ll end up kicking yourself if don’t have them. Especially as nostalgia becomes more and more profitable. As preservation comes in many forms (keeping copies of entire games, saving individual assets, and keeping record of exterior development materials), it’s vital to know that committing to as many preservation efforts as possible will yield benefits in the long run. Even though a number of industry professionals were consulted for this piece, with each coming at the value of game preservation from different angles, every one of them had the same core message: save your work. The logistics of this task, revolving around terabytes of game data, are obviously more complex than just simply saving work as you go along. That said, any Google Drive with development documents, or individual assets backed up onto a hard drive, will go a long way down the line. Every story of lost game data should serve as a warning. “History allows you to avoid mistakes, and to repeat successes,” explained Rob Curl, a museum historian at the Museum of Art and Digital Entertainment (MADE) in Oakland, California. This might sound simple on the surface, but having quick access to a plethora of games to help you understand the mistakes and successes of a particular genre, theme or franchise can’t be achieved if those titles aren’t preserved or collected properly. Maybe you’re tackling a genre or mechanic you’ve never attempted before and want to access its history from the very beginning? Well, as Curl told me, proper preservation can help with that. “A few years ago, when a brand new snowboarding game was being developed, the staff had a simple but difficult request for it because they wanted to play every single snowboarding game that had ever been made,” said Curl of a studio that came to the MADE. “So they sort of created for themselves, this sort of internal research about how all this stuff had been done before,” explained Curl. “And so therefore, they have a sense of what they can do that’s new or different. And if you don’t have those two things working in concert with each other, you just have folks who repeat mistakes that have been done in the past.” Requests like this aren’t simple, of course, with decades of games and their corresponding hardware needing to be collected, catalogued, and preserved for any organisation to successfully present them as a complete package. Without community-wide preservation, a number of the titles in this scenario could be missing, damaged, or just completely inaccessible after a decade or two – and yet the value of collecting them on the development process cannot be understated. Whilst that example is more toward the extreme side, Curl also looks at it from a more micro perspective, and how individual games and tropes, if still approachable after long periods of time, can successfully be used as an influence during development. “The only reason that Undertale can do what it does in terms of speaking to the meta and talking to the player, that stems from Earthbound and other games that have this sense of like, ‘oh, right, this is a video game,’” Curl explained. “The only way that you can successfully iterate on something is to be aware of what the trope has done in the past, right? “Why would you do this? It’s because if you want to build a legacy, if you want your stuff to be worth something in the future, you need to be able to pull on those assets, pull on those on that code, pull on that history, and that work that you did in order to make the sequel, right? In order to do the remake in 10 or 15 years. “Nostalgia is a powerful drug […] if you want to help capitalise off of that emotion that you can engender in people, then it’s real dang important that you don’t throw away the process by which you helped them make those memories in the first place, it needs to be preserved,” Curl added. For preservation to be done right it needs to be a community effort, and as Curl explained, committing to can benefit the industry as a whole, alongside developers coming back to classic franchise after years away. When talking about preservation, it’s equally as important to understand and hold onto the materials that exist outside of the game itself. Safeguarding the ability to look at the wider context of a game before and after its release is equally as important as during the development process itself. Dr Michael Pennington is the digital and projects curator at the National Videogame Museum in Sheffield, UK, and he believes that these paratextual materials – which exist outside of the main product but still in tandem with it – should be preserved as well. “These materials exist outside of the game but inform how we make meaning from them, and inform how we played them. Paratextual materials speak about the game without existing within the game itself, and are absolutely crucial to our preservation efforts,” Pennington explained. “There’s a tiered way of looking at it,” he added. “On the industry side it’s understanding how a product was made and its different commercial contexts, how it was advertised to fans, pitched to stakeholders and how it was developed.” Harnessing these materials as both the developer and publisher of a game can help preserve why your game came into existence in the first place, and inform whether or not things like remakes, sequels or downloadable content make sense in the time that’s elapsed since the initial release. “Another key side of the collection of paratextual materials is that fan-led work,” continued Pennington, “because you can extract more meaning from how the game was received and how it lived on after it was released.” Pennington describes these fan-led materials as things like online strategy guides, Twitch or YouTube footage, mods and even memes. Internally preserving the cultural impact of your game after it’s been released might seem like a daunting task with little in the way of tangible rewards, but discerning how your community plays and interacts with your game can help you feed back into that with follow up content. As noted by Pennington: “Digital objects like playthroughs show how the game was played, and how meaning was made”. Whilst this might seem unimportant at a glance, understanding and preserving this history of your game can serve further releases down the line. At their core, preservation efforts need time and resources, and whilst these roadblocks are easier for triple-A studios and publishers to overcome, smaller indie developers that really need to stretch their budget are putting preservation, understandably, low on the priority list. This sisyphean struggle can’t be managed by indie developers alone, and non-profit game preservation organisation HitSave! exists as a way to both help smaller studios preserve their games, and illustrate how this can benefit the industry as a whole. “One really cool thing that we were able to get from the Wintermoor Tactics Club team was the translation planning documents,” explained HitSave! executive director Jonas Rosland. “Because it’s a text heavy visual novel with battle mechanics, tons of text and jokes don’t translate into other languages. So by having a bunch of documents around translation of the text and everything like that, people can see what it actually takes to translate a game.” Efforts like this mean there’s now a wealth of documents surrounding Wintermoor Tactics Club’s development, which other indie studios can consult to help them understand how teams of similar scope, size and ambition dealt with specific development problems. For example, the way a triple-A studio localises and translates a game may have similarities to indie developers, but by virtue of the drastic differences in staff numbers and resources, indie studios will take a different approach. Having the related design documents then creates a streamlined way for more indie developers to understand how those who came before them have tackled specific problems, and done so within similar constraints. “We want to help researchers who are researching games because some of the people behind these fantastic indie games might go on and become triple-A directors one day,” notes Rosland. Rosland also understands that preservation isn’t that simple, as certain documents will often need to remain under wraps for some time. That said, HitSave! exists to get the stories and lessons from indies whilst the iron is hot, and to hold onto them until they can be made public. “We want to focus on what’s happening now,” said Rosland, “so we don’t have to hunt them down in 20 years. So people can go through it now, and they could go through it in five years and 10 years and 20 years, and it will still be the same content.” Even if all of these documents aren’t made public for a long time, having the stories and decisions recorded when fresh in a developers mind is much better than decades later, after they’ve likely shipped a number of vastly different titles since. Raising Kratos - the behind-the-scenes documentary that chronicles the herculean development of the 2018 God Of War reboot – shows that a mammoth franchise can undergo drastic change and be successful. Of course, not every game can have a 2-hour documentary documenting its development cycle, but the practice of preserving development history presented by Raising Kratos should be taken on board. It’s better to get the documents, interviews and information as it’s being explored, rather than a decade later. Preserving older games has already been paying off for big names in the industry, with Nintendo bringing back Star Fox 2 after two decades for the Super NES Mini and to drive Nintendo Switch Online subscribers. The act of preservation has had direct links to when players start clamouring for a nostalgic hit – à la Wind Waker on Switch – as it allows developers to open up the vault and find archived materials and assets that can either be repurposed, or in some cases even re-released. Video game preservation is about more than just holding onto the blink-and-you’ll-miss-it pace of this industry. It presents a clear cut way to learn from mistakes and successes, to bring older games forward through remasters, remakes, reboots and sequels, and provide context for the social and economic states that a game is released in. Having resources readily available, instead of having to work around the bare minimum of preserved materials, can only help development projects down the line. Whether it’s your own, someone else’s, or a continuation of something you worked on decades ago, preservation of contemporary materials will only serve to benefit games. It’s also nice to be able to observe and learn from our history – instead of it being lost forever.